Recently, Canada has seemingly had a bit of an issue when it comes to our institutions and their ability to get the results they want. Economic productivity is reportedly low, which, avoiding the fact that productivity is a dubious measure in itself, has become a big talking point. This is what people are blaming for stagnant wages. Many cities have also seemingly been unable to develop anything substantially new. Until extremely recently, two weeks ago as of writing this, Toronto managed to develop and grow for 23 years, increasing its population from ~4.5 million to ~6.5 million, all while reducing the amount of subways it had. This involved closing the line 3 after a derailment in 2023, after running on out-of-date hardware for some 15 years. The Eglinton Crosstown has been under construction for 15 years, and the Finch West Extension finally opened to poor results (the trains run slower than the buses they replaced and costing in at only $3.7 BILLION) in late 2025.

The government seems to be attempting to solve this apparent complete failure of results in one way: by stripping regulations and workers’ rights. More sacrifice from the workers for maybe potentially some later gain and a few more jobs. In Ontario, Carney and Ford are teaming up to ensure that select private companies will be able to ignore laws and regulations to develop faster and hopefully get us on track to where we “should” be in their eyes. Don’t worry about climate change; we plan to miss all our goals. Don’t worry about the environment or homes of endangered species; it can be clear-cut to make a toxic dumping ground. Don’t worry about workers' rights; we need more profit.

This is one attempt to solve the issue, one that is distinctly pro-capital and big business. If you are big enough (with a successful enough lobby to get a contract), you can get selected to break the rules set out for everyone. If some people get to break the rules, what is the point of having universal rules? All this is to say that the democratic process is changing. In this case, they are becoming less “of the people”. This is the state merging with corporations, the economic model that defines fascism, employed by liberals during crises in order to maintain capitalism.

This is being done to “cut through bureaucratic bloat and red tape”. The idea is that the process holds back our development: that skipping it and developing without feedback would be better for the people no longer involved in the process. In times like these, we need to make “touch choices” to “get what needs to be done, done.” People often seem to ignore that giving a bourgeois state unchecked power just means you will get forced into bourgeois results! This talk of these tough choices, however, seems to skip over something completely: If the process is broken, and we need to allow specific companies to ignore regulations and processes to get anything done, why are we not directly addressing and evolving the process? While the real answer sits somewhere around protecting profits, we should still look into how the process works and what something else could look like if we want to have even a hope of implementing something better in the future.

I am going to approach this through a very narrow lens: my discussions in the process of the bike lanes on Sloane, as well as other recent discussions I have had to use as examples.

As a Toronto waste yute, witnessing our development is pretty crushing. The economy seems bad for workers, who struggle to live comfortably and are constantly told to sacrifice for the greater good. This greater good seems to never materialize, or if it does, is so loaded with half measures or absolute failure that you wonder why it was even done in the first place. Recently, I have been attending meetings related to bike lane development on Sloane Avenue, and watching this process and talking to the people has given me a little insight into how this comes to be.

First, I will start with a discussion I had many months ago that prompted an article that got lost in the sauce and didn’t make it out of the sticks: I was talking with a health and safety consultant at work. She mentioned how long it took her to get to our meeting, as is a usual conversation in Toronto. I gave the usual platitudes about “yeah, traffic, amirite!” She asked about my travel and how I find getting around these days. I said I have an electric bike, so I can zip around all the way downtown without any lights or anything. It’s quick, convenient, and consistent, which I like. This comes at the cost of winter inconvenience and some places being dangerous due to a lack of infrastructure. She generally just gave me a remark of disapproval about bikes and said she’s a car person, so we should avoid the topic. It was a bit strange. Later, she also said she was really against working from home and thinks people need to get back into the office. I also found this particularly strange. To summarize: she hates traffic, but wants more people moving around all the time, and wants less alternative transportation. She hates traffic, but the result of each thing she wants is more traffic.

On to the bike lanes meeting on Sloane. Unfortunately, I had an event at the same time as the initial proposal, but I was able to make it to the consultation, where people could give feedback. For reference, the road is full of potholes, extremely wide, and frankly, about as falling apart as a road can be in a city. It is up for redevelopment, so it will be redone completely, no matter what. The question is how it will be redone. Currently, the road has one lane of traffic each way, some parking in certain spots, and a bus. The plan would add separated bike lanes, keep all lanes of traffic, keep all parking, and keep the bus with approximately the same stops. This was all laid out wonderfully on some big maps that made the redevelopment easy to see in its totality. People in the community had complained about the safety of the street (especially at the elementary school), the speed of cars on the road, and people on scooters zipping around everywhere with no regard for the rules of the road.

All of these are addressed in the plan. The bike lanes would help kids bike to school safely, reducing traffic and also offering a safer drop-off zone for the buses. Narrowing of lanes would help reduce the speed of cars, and having a bike lane would get non-car methods of transportation off the roads. It also brings the road up to date with what has been successful all around the world. All this while not reducing any car lanes, and maintaining all the parking that was there before. People must have loved that their issues were addressed and engaged with the plan to pick up on specific details and see how it all works, right?

Well, not at all. Instead, the consultation was packed full of people yelling at random school staffers, people who could barely walk, talking about how “as an avid cyclist” they “just don’t think it’s right”, and asking for the entire development to be called off. This would mean instead of losing nothing, improving the street, and having all their problems addressed, they would rather the road remain full of potholes. These are the NIMBYs, and we know these types. They preach that every development is a disaster, fight against it any way they know how, and if the development gets through. None of their fears ever materialize, but they WILL keep on fighting.

I spoke to my councillor about these people, right at a time where most working people could discuss things: his office discussion event at 9:00 AM on a Monday.

It’s easy to say something like “Democracy could be good, but the people are stupid” or “we need a strong leader to make decisions for us”, or even just say that “we just need someone to finally force some change through for this one”. It’s also easy to say “we just need to overthrow capitalism and have a real, equitable world”. I think these are easy cop outs to actually addressing a problem. The first calls for outcomes in a way that is not equitable, which will only serve to ensure that non-equitable outcomes can’t be punished. In the second, ok, so what will that process look like?

Here, I will outline a process different from the one we have that addresses the key flaw: people seek both means and outcomes that are contradictory. This guarantees poor outcomes. There are two goals in a new system: Better outcomes and a means that aims to ensure outcomes are equitable. I don’t see them as contradictory.

One thing our system does extremely poorly is guarantee quality outcomes. Decisions are made, they are abject failures, and we follow them up by making the same (or worse) decisions. Projects are completed, fail to do what they are designed to do (or even make the problem worse), and the same decisions get made for the next project. This is a symptom of some of those means issues. People who do not understand the problem are a part of how we decide to solve the problem. Traffic? Add more lanes. More lanes didn’t solve traffic? Clearly not enough lanes, add more. Some solutions make sense if you think about it for a couple of minutes, but the world is pretty complicated, and often these “intuitive” solutions simply do not work.

This could be replaced with a process. People are asked about what outcomes they want for a specific project. Meetings are held, and a broader consensus is made on where priorities are and what metrics would be primary indicators of success (other metrics would obviously still be tracked). From here, experts in the subject field (city planners, etc) create a plan that addresses those issues, execute the plan, and after varying amounts of time, take surveys about the results of the plan according to metrics. Surveys can also include perceptions of the plan and non-specific community satisfaction. The results of these surveys are relayed back to education on city planning, where researchers would adjust models based on the new feedback. Changes would be made, more projects would be done, more priorities and metrics would be set, more plans executed, more input would be cycled back, etc.

Projects could get a certain number of “marks” based on the successes and shortcomings of the plans. Sections of the plan deemed successful could be positive marks on the record of planners who supported it. Sections riddled with issues or receiving negative feedback could be negative marks on the record of planners who supported it. Plan proposals that do not receive support mean that planners do not have faith that they will achieve desirable outcomes, and the plan should likely be redeveloped. Positive and negative reviews for planners would be based on broader trend lines. One plan gone wrong for one reason or another should not harm a planner’s career, but rather consistent failure to achieve desirable results should make them revisit what we know works.

- A scope or plan for the project is laid out (similar to now)

- Get community input

- Decide priorities

- Decide focus metrics

- Create a plan that accomplishes what the community wants

- Note: You could get community feedback for small changes here, but the larger core of the plan must stay the same

- Execute the plan

- Survey results at different intervals after completion (including shorter and longer term)

- Measure target metrics and other surrounding metrics

- Survey perceptions on the planning and execution of the plan

- Gather subjective input on the results of the plan

- Gather broader input on quality of life

- Use the results of the plans to update models and education for future planning

- Based on results:

- Good results can be positive marks on the planner’s record

- negative results can be marks against

- too many marks against and education must be redone for a period of time, where the person can not create or execute more plans until they are re-certified

What is the result? Here is what I have broadly broken down for city planners:

- City planners would be able to execute plans based on what people want.

- Plan execution could be uninterrupted and decisive.

- People who do not understand city planning are not able to destroy quality plans.

- City planners would be focused on making projects that benefit the communities they work for.

- City planners who consistently do projects that communities don’t like get removed from the pool of selectable city planners.

- City planners are kept up to date on the latest, and consistently successful city planners don’t need to worry about that since they’re successful anyway.

- City planners are given tools to re-entry if it is their passion, but they didn’t quite land their first shot.

This model could similarly be applied to other fields, like economics.

- Economists make predictions and prescribe policy on a region (differing regions may have different policies enacted at the same time)

- Goals and metrics are defined and agreed upon

- Policy is enacted, and results are monitored

- Surveys are done, metrics are collected, input is received, and quality of life input is received

- According to these, policies are measured against each other

- Bad outcomes are deemed failures, good policies are assessed, changes made, models updated, and the process begins again

Economists who prescribe bad policy for the majority get filtered out, two separate good policies can be assessed for their benefits, and economies are made better gradually for the majority. People get input and the results they want, while getting rid of the part where they can demand results, then destroy their own results by being insufferable. Plans can be executed faster with less interference at every step.

Since this is almost certainly not going to become our real policy, and is mostly just me creatively complaining, I don’t want to get too into the weeds, but it is necessary to address potential shortcomings of the system as outlined. Some of these may happen, some may not, some are the same as now, and some aren’t even actual problems of the system at all. It’s a necessary step and worth thinking about potential problems as an exercise, dialectics or whatnot, but I’m not here making hundred-page bills, I’m here making something I hope my friends will like reading.

Pigeon Holes and Risk Aversion

This policy rewards doing something that people will receive well, and broadly moves forward in a kind of alpha-beta testing strategy on the academic side of things. This could lead people down a specific “branch” of policy prescription that is good, but another branch is better. People may not want to take risks and try something new because this one is ol’ reliable, or ol’ reliable may continue to be used even after structural progression beyond its ideal use case.

I always tell people you can’t let perfection get in the way of something good. Right now, we will consistently do things that are actively bad for the majority. The new system is thus an improvement. Additionally, if there is a new consensus amongst the studied planners, they can agree to execute the plan and check the results, potentially dedicating money to re-developing to the “main” branch of ideas if it does not work out. One plan does not dictate the career trajectory of the planners; it’s about trends and consistency. If something is tried and fails, a regression to something tried and true is not necessarily a bad feature. I like some experimentation in my life, but consistency is also healthy.

Selection Process

Who gets to go to the meetings where goals and concerns are voiced? This is a problem now and would probably also be a problem in the new system, and I don’t think it can be truly solved. It is the contradiction between freedom and domination. Give people freedom of choice to show up, and they can freely choose not to.

Broadly, handle it as it should be handled now. Flyers sent out the the community, have different meetings at different times of different days spread out over a month or so, get feedback, and move on. People can show up if they care, or not if they don’t care about this specific thing. Allow them to write in, send an email, or do a digital survey. Someone could live 2 blocks from a road being redeveloped and never take that road, making them also not helpful if they do show up to the meeting under any mandatory jury-duty-like condition.

NIMBYs / Loud Minorities

What about groups of people who absolutely love showing up and hating on plans? I believe this new strategy is actually better than now for a couple of reasons.

Firstly, many of these people know the outcomes they want, but just hate it when things actually happen around them. They want better traffic flow while having safer and better designed entries and exits for school traffic. The problem is that when they see what that looks like, they hate it when it looks different from what they know. Here, they can say what they want, have it built into the plan, but be removed from the process until it is done.

Right now, these people are given opportunities to change plans at several steps. By removing them from the steps where they are most destructive, they are not able to jam up the entire process forever. Their initial inputs are received, then a real plan is executed, and the new strategy stops them from creating infinite half measures or bad decisions that cause end-result failue.

Metrics Becoming Targets

This could actually become a problem in this system, but it is also a problem of our current system, where we can’t even meet metrics in the first place. Given metrics and planners with careers on the line, what stops these planners from optimising around certain metrics?

My main counters to this are having the community have input on success metrics as well as having a secondary and differently “weighted” subjective feedback attached. Having community input on metrics stops the process from getting completely focused on having one metric dictate everything, even if it doesn’t necessarily help people (think GDP). Having the subjective feedback helps with trying to figure out what new metrics or adverse effects may be present that aren’t represented using the currently measured metrics.

What if people think certain metrics will have certain impacts on them that don’t actually happen (think GDP)? Having room for more than one metric is my main attempt at resolving this.

What if metrics are broadly at odds with each other (Think right now with house prices vs home values)? Which will take priority in success metrics? I think part of the process here is that it would be harder to develop into these places in the big picture, but frankly, this is a tough spot off the dome that would require professionals from several areas to address. Luckily, this system allows that, unlike the current one, where the bourgeois interest is always taken.

Mass Insistence On Bad Decisions

What happens if everyone in the system for one reason or another wants decisions with bad outcomes, from the planners to the people being consulted in the process? Not only does this happen all the time right now, but metrics and subjective experience would show this over time, and the planning decisions would be culled, as it forces learning from the evidence rather than just vibes or promises.

If only the planners insist on bad plans, the poor results would force them back to school so much that they would lose representation in the moment and also not be able to sustain themselves because they would now only be spending half their career getting re-certified.

The people can’t really insist on bad plans in this system.

Existential Shocks

What happens if something, like a pandemic response, means the plans don’t really get a fair shot? In these cases, surely, good plans would receive negative feedback. Board reviews could be done to account for this, which would then in turn open up more opportunity for more bad plans to get away with sticking around for longer, but existential shocks I see as a real potential shortcoming. It is also a shortcoming for most systems like this, including ours today. I think doing planner reviews as a trend line and not a “three strikes” or “one bad plan and done” helps people get through shocks, and having short as well as long-term measuring of outcomes makes it more likely that a shock and recovery are both accounted for at some point in the review cycle.

Cross Contamination

What if other plans cross-contaminate and muddle feedback, or if two otherwise good plans happen to not blend well together? I would have to assume that under this system, cross-contamination would be near constant. I think this is mostly a problem of thinking of this system as a one-off, isolated event. If the system were working on a larger scale for a consistent amount of time, good and bad plans would be selected for and against, and cross contamination for different projects would be something planners would be constantly studying and building in as the process continues to evolve. Thinking once again in branches, there may be a branch that is optimal in one scenario, but another branch that tends to work better in another. The point is that people who study and understand this are part of the selection process.

Keeping Communities Unique

First, I would just like to state out front that I think if people had communities that improved over time in favour of their best interest, people would probably care less about their specific neighbourhood being “unique”. I think if there were a system that people could trust, a lot of attitudes would change over time. I do think having different communities is cool. Aesthetics could easily be made part of this process, for example, a development near brick works could be specifically mandated to need to have exposed brick integrated into its style. Generally speaking, there is also subjective feedback. If planners want more positive feedback, the feel of the community is something they would want to preserve and have people be proud of to appeal to residents of the area.

Do It In Another Community

What of things that are broadly seen as negative, like a homeless shelter that people may not like, but needs to happen? Right now, we simply struggle to get these things done anywhere at all. If development were done in favour of the majority of people, these types of developments of last resort would likely need to happen less often.

Alas, it may still need to happen. Under this system, for starters, it would actually happen, as the community would just give overall feedback on how it would be brought about and how to make sure it goes well, not destroy the entire plan.

For reviews, some development may just be fundamentally deeply unpopular. In this case, good planners may need to be assigned to make it simply have as many upsides with as few downsides as possible, or it could be made a smaller part of a larger development to offset it. I would call this a definite weak point of the process, but it is a definite weak point of our current process as well.

Some of the astute among you may have noticed that I have re-invented democratic central planning in one form or another. This brings me to a brief discussion I want to include about reform and revolution, as well as organic marxism and process thinking.

For reform and revolution, we often joke about the concept of “voting your way to a revolution”; We have a bourgeois state, and as such, the bourgeois state will not ever concede the ability for voters to vote for a proletarian state. Then comes the alternative: do a revolution. There will be chaos, and in the midst of all the chaos, your ideology will win and rise. This is also funny, because people think their ideology will rise from the ashes, when the reality is that my ideology will rise from the ashes. I think many people who want revolution don’t necessarily express themselves well on what revolution actually looks like and how it could be done on a global scale.

The focus of my fascination with post-capitalism and bringing about new systems is found on a few fronts. One of these is likely sourced in my influence from Mark Fisher: making other systems tangible. I want to imagine new systems, outline them and some of their processes, think of where they might succeed and what shortcomings they may suffer from. This leads to others. What systems, if put in place, may mimic or mirror our current system in surface-level function, yet inevitably lead to changes compatible with post-capitalist or socialist desires? If you were to do a revolution (whatever that entails), what systems could you put in place to ensure progress towards your goals while making compromises to either reduce the likelihood of a successful reactionary counter-revolution or the necessity of having to rebuild an entire modern economy from scratch in one day, all while not getting conquered?

Compromise is necessary one way or another, but you don’t have to compromise on everything. This system I focused on is mostly through the lens of making it so that bike lanes are actually installed, but I did outline briefly how the exact same system could be used for economic planning. This economic planning is separate from and replaces bourgeois economic planning, but in terms of people’s interaction with it, the changes are nearly invisible. Bourgeois economic planning is able to assign austerity over and over, implementing a neoliberal model that doesn’t even succeed in its own internal logic. This planning, seemingly very similar, necessitates positive outcomes as reported from the majority, so things like austerity cease to be a feasible policy prescription.

I remember speaking to Bennet a while back. We were talking about systems like worker co-ops and their shortcomings, as well as my defence of them despite historic criticism. My defence of worker co-ops stems from a simple principle: they are incredibly easy to imagine for your average person, they offer more agency for your average person, and if everything was suddenly a worker coop, why would people decide to bring back private ownership? The decision to bring back private ownership stands only to make people lose agency for no gain. Socialist structures like worker co-ops, which are market companies owned by workers, have been measured as more efficient than private ownership with better outcomes, so they suddenly become possible under democratic planning like this. If this worker co-op replacing private ownership scenario were to happen, you would eliminate private ownership of the means of production. From there begins work on what comes next. There are still criticisms to be had by all means, but they allow the opportunity for further changes impossible under the current system.

Systems like these are alternatives to capitalist forms without thinking of alternatives to capitalism as “giant government no freedom” that permeates the discourse so much. The system of planning outlined above is familiar; it resembles the process people know. Hell, it could even be implemented under capitalism without drawing too much attention. It may also offer better results in the way people seem to currently desire and not be restricted to bourgeois outcomes. Instead of having a government pick corporations as big winners, it rather promotes outcomes that support the masses.

When the ruling class tell us that we need to strip away workers’ rights, environmental protections, and indigenous sovereignty to get things done, it isn’t because they want to get things done. It is because they want to strip away workers’ rights, environmental protections, and indigenous sovereignty. Other options are easy to imagine and available. They simply prefer fascism because it’s good for their material interests. Don’t fall for it.

Thanks for joining me on this exercise.

Sankofa say look to the past to find our wisdom replenish as intuition

There's growing pains and I know that's nothing that you don’t know

If we only knew our mistakes then I’d kick us in the ass

Oncle

System Erasure is a tiny game development studio based in Finland. The only two members of the team have so far managed to create two staggeringly different entries into their repertoire. The first is the high octane shoot-em-up 'ZeroRanger' where the player is tasked with being the sole defender of earth against an overwhelming alien fleet. The second being the far more subdued sokoban (block pushing) puzzler where the player delves deeper and deeper into a cryptic labyrinth in search of something at the bottom. While on the surface these two experiences seem to hold little in common with the other, astute individuals will notice peculiar details amongst the sparse store pages of both of their games. What kind of shoot-em-up would include “mystery” as one of the major selling points of the game? Why does the seemingly medieval fantasy presentation of Void Stranger's trailer contain a cutaway of what seems to be a mech? Indeed, there is more to investigate on those fronts but I will not discuss these things in depth. Instead, the spotlight will be on the major thematic connection that underpins both games regardless of gameplay or setting. Both of System Erasure's games want you to give up and succumb to despair.

System Erasure is a tiny game development studio based in Finland. The only two members of the team have so far managed to create two staggeringly different entries into their repertoire. The first is the high octane shoot-em-up 'ZeroRanger' where the player is tasked with being the sole defender of earth against an overwhelming alien fleet. The second being the far more subdued sokoban (block pushing) puzzler where the player delves deeper and deeper into a cryptic labyrinth in search of something at the bottom. While on the surface these two experiences seem to hold little in common with the other, astute individuals will notice peculiar details amongst the sparse store pages of both of their games. What kind of shoot-em-up would include “mystery” as one of the major selling points of the game? Why does the seemingly medieval fantasy presentation of Void Stranger's trailer contain a cutaway of what seems to be a mech? Indeed, there is more to investigate on those fronts but I will not discuss these things in depth. Instead, the spotlight will be on the major thematic connection that underpins both games regardless of gameplay or setting. Both of System Erasure's games want you to give up and succumb to despair.

my steam wishlist, there's like 55 games on there

my steam wishlist, there's like 55 games on there

thumbnails of Daryl's four backlog videos

thumbnails of Daryl's four backlog videos

In this we can see that the kicking form of football has already become significantly less violent that its ancestor game of Harpastum, even before the Cambridge rules neutered it totally. Even so, it seems that while you could not tackle your opponent outright (“therefore there is a law that they must not strike higher than the ball”), you could still trip them down. Willughby describes the carrying game – which he refers to as hurling – as follows:

In this we can see that the kicking form of football has already become significantly less violent that its ancestor game of Harpastum, even before the Cambridge rules neutered it totally. Even so, it seems that while you could not tackle your opponent outright (“therefore there is a law that they must not strike higher than the ball”), you could still trip them down. Willughby describes the carrying game – which he refers to as hurling – as follows:

Red harvester ants. So cute!

Red harvester ants. So cute! making this image was painful

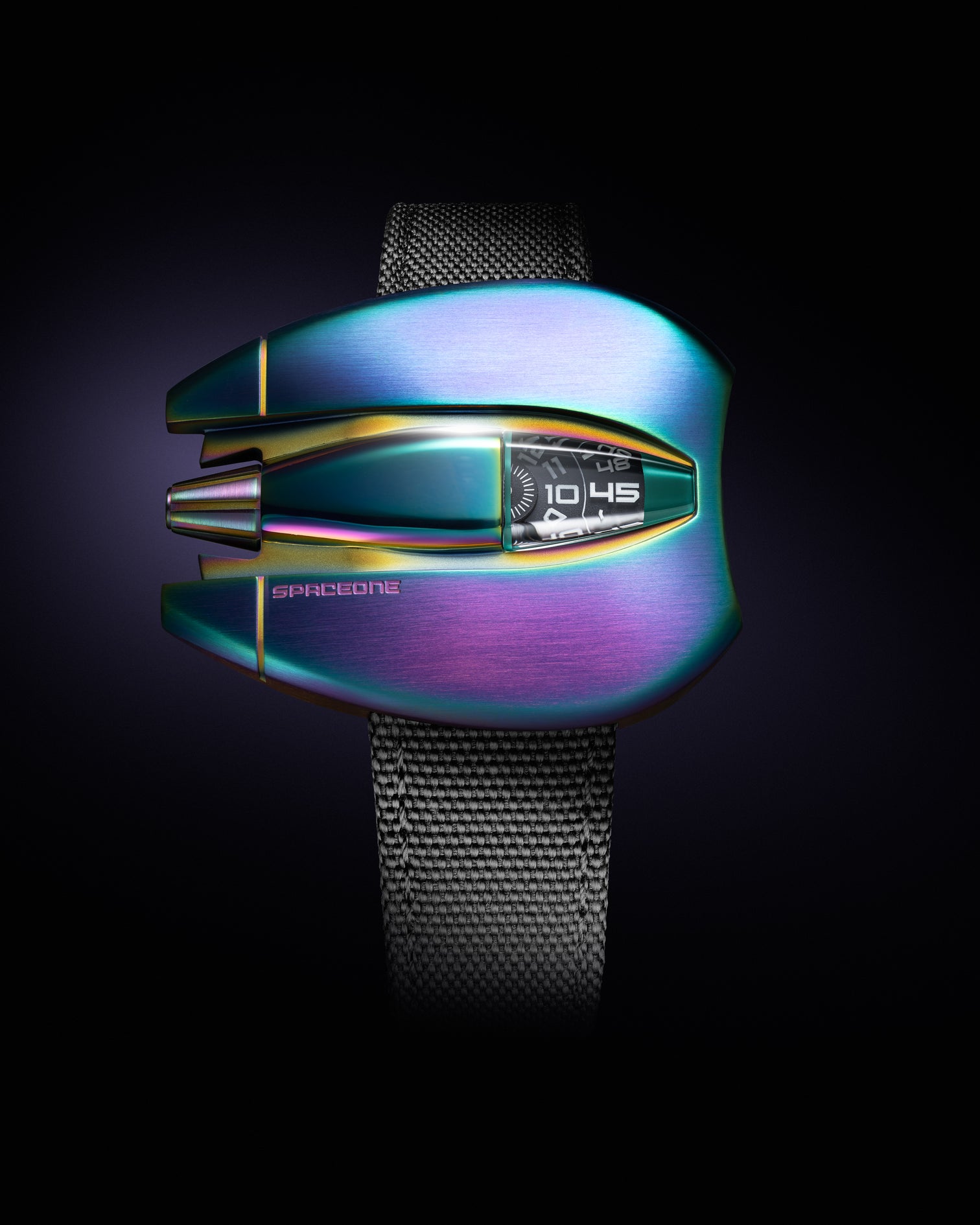

making this image was painful the original was lost, this is the contemporary version, still by Breguet (the brand not the dude this time)

the original was lost, this is the contemporary version, still by Breguet (the brand not the dude this time)

this definitely fits

this definitely fits refresher on watch dimensions

refresher on watch dimensions

BVLGARI Serpenti Secret Watch and Micromilspec Milgraph

BVLGARI Serpenti Secret Watch and Micromilspec Milgraph

All in all, I only got ~3.5 years of solid training under my belt, and 2 years of consistent training is my longest training streak. I mean to break that.

All in all, I only got ~3.5 years of solid training under my belt, and 2 years of consistent training is my longest training streak. I mean to break that.

exercises grouped together with colours are supersetted, and the numbers are the number of sets

exercises grouped together with colours are supersetted, and the numbers are the number of sets

The dark purple line is my measured weight, the weight on the scale I enter every morning, and the light purple line is my extrapolated “real” weight according to the app. At least with macrofactor I don't have to bother making graphs

The dark purple line is my measured weight, the weight on the scale I enter every morning, and the light purple line is my extrapolated “real” weight according to the app. At least with macrofactor I don't have to bother making graphs